BY ZAIN ALI

Introduction

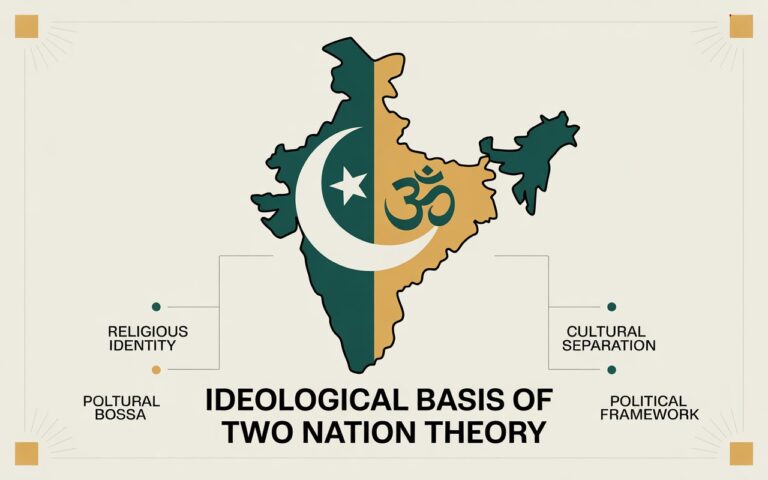

The Two-Nation Theory emerged as a defining ideological concept in the history of the Indian subcontinent, ultimately shaping the creation of Pakistan in 1947. Rooted in religious nationalism, the theory proposed that Muslims and Hindus were not merely followers of different religions but constituted two distinct nations, each with its own social, cultural, and political identity. This idea was fueled by the socio-political conditions of British India, the decline of the Mughal Empire, and the rise of Hindu-majority political movements such as the Indian National Congress.

Historically, Muslim India had developed a rich and distinct cultural heritage. The amalgamation of Persian, Central Asian, and Indian influences gave birth to a unique Indo-Muslim civilization, evident in architecture, literature, and customs. Intellectuals and reformers like Ahmad Sirhindi (1564–1624) and Shah Waliullah (1703–1762) emphasized the distinctiveness of Muslim identity within India, advocating for the preservation of Islamic traditions and self consciousness in the face of a changing socio-political landscape. The advent of British rule further complicated Hindu-Muslim relations, introducing Western education, administrative reforms, and new political ideologies that highlighted communal distinctions

By the 19th century, prominent figures such as Syed Ahmed Khan and the leaders of the Aligarh Movement began articulating the need for Muslims to assert their distinct identity. Syed Ahmed Khan argued that Muslims, with their unique historical, religious, and cultural experiences, could not mergeb fully into the political and social framework promoted by the Congress, which emphasized a composite Indian nationalism. His advocacy for modern education among Muslims, combined with a reinforcement of Islamic values, laid the intellectual foundation for the Two-Nation Theory. The theory was later politically mobilized by Muhammad Iqbal, who envisioned a separate homeland for Muslims, and translated into reality by Muhammad Ali Jinnah through the Pakistan Movement.

The Two-Nation Theory, therefore, was not simply a call for political separation but a comprehensive ideological framework. It argued that Muslim and Hindu ways of life were inherently incompatible, making coexistence within a single political state fraught with conflict. Cultural, religious, social, and legal differences were cited to justify the creation of an independent Muslim homeland where Muslims could govern themselves according to their own traditions while ensuring equality and justice for all citizens within their territories.

Could Hindus and Muslims Form One Nation?

The central question underlying the Two-Nation Theory was: Could Hindus and Muslims, despite centuries of coexistence, truly form a single nation? Proponents argued that the answer was no. Muhammad Ali Jinnah, addressing the All India Muslim League in Lahore in 1940, famously stated that Hindus and Muslims belonged to two different religious philosophies, social customs, and literary traditions. They neither intermarried nor shared cultural practices extensively, and their historical narratives often positioned each community in opposition to the other.

A quote from Jinnah’s speech on March 22, 1940, illustrates this perspective:

“We maintain and hold that Muslims and Hindus are two major nations by any definition or test of a nation. We are a nation of hundred million and what is more, we are a nation with our own distinctive culture and civilization, language and literature, art and architecture, names and nomenclature, sense of values and proportions, legal laws and moral codes, customs and calendar, history and tradition, and aptitude and ambitions. In short, we have our own outlook on life and of life.”

The theory was politically institutionalized by the All India Muslim League, which demanded separate electorates, political representation, and ultimately a sovereign state for Muslims in the northwestern and eastern provinces of British India. Figures like Iqbal and Jinnah argued that only through political autonomy could Muslims preserve their distinct identity. They believed that Hindu-majority India would inevitably dominate politically, marginalizing Muslim interests and threatening cultural survival.

Support for the Two-Nation Theory, however, was not universal. Hindu nationalists, including Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), also recognized Muslims as a distinct community but envisioned India as a Hindu nation. Conversely, leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan opposed partition, advocating for composite nationalism where Muslims and Hindus could coexist within a unified India. The All India Azad Muslim Conference represented nationalist Muslims who rejected the theory, emphasizing shared Indian identity over religious distinction.

The historical foundation of the theory was also debated. Some historians argue that it was largely an elite-driven movement, championed by politically influential Muslims, while the majority of the Muslim population remained neutral or opposed to partition. However, British policies of “divide and rule,” Hindu revivalist movements like Arya Samaj, and socio-economic disparities fueled communal consciousness, creating conditions that allowed the Two-Nation Theory to gain mass political support. Key intellectual and religious endorsements further strengthened the theory. Scholars such as Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Muhammad Iqbal, and religious leaders from the Barelvi community argued that Islam provided a complete code of life incompatible with Hindu social structures. They maintained that Muslims required a separate state to freely practice their religion and safeguard their political, cultural, and economic interests. The Deobandi scholars were divided; while some opposed partition, others, such as Ashraf Ali Thanvi, justified the creation of Pakistan on the grounds that a unified India would dilute Islamic identity.

The partition of British India in 1947 into India and Pakistan marked the practical application of the TwoNation Theory. The creation of Pakistan as a homeland for Muslims validated, in the eyes of its proponents, the argument that Hindus and Muslims could not coexist within a single nation. Nevertheless, the subsequent emergence of Bangladesh in 1971 and the presence of a large Muslim minority in India challenged the absoluteness of the theory, demonstrating that religious identity alone could not fully define nationhood. Modern scholars continue to debate the theory’s relevance, its historical accuracy, and its socio-political consequences.

Conclusion

The Two-Nation Theory occupies a central place in South Asian history as the ideological justification for the creation of Pakistan. It combined religious, cultural, and political arguments to advocate for the separation of Muslims from Hindu-majority India. Figures like Syed Ahmed Khan, Muhammad Iqbal, and Muhammad Ali Jinnah provided both the intellectual and political frameworks for this idea, arguing that Muslims required a distinct homeland to preserve their identity and interests.

Opposition to the theory was significant, both from Hindu leaders and Muslim reformers who promoted composite nationalism. Gandhi, Azad, and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan emphasized unity, shared history, and cultural commonality between Hindus and Muslims, arguing that partition would cause unprecedented human suffering. Post-partition events, including the creation of Bangladesh, have sparked debates about the theory’s practical and ideological validity. Critics contend that the theory primarily served elite interests, led to massive displacement and loss of life, and failed to create a homogeneous Muslim nation.

REFRENCES

- Jalal, Ayesha. The Struggle for Pakistan: A Muslim Homeland and Global Politics. Harvard University Press, 2014.

- Qureshi, Ishtiaq Husain. The Struggle for Pakistan. Oxford University Press, 1983.

- Jinnah, Muhammad Ali. Speeches and Statements of Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Compiled by the Government of Pakistan, 1940.

- Talbot, Ian. Pakistan: A Modern History. Hurst & Company, 2009.

- Burki, Shahid Javed. Pakistan: Fifty Years of Nationhood. Westview Press, 1999.

- Rashid, Ahmed. Pakistan on the Brink: Politics, Society and Islam. Penguin Books, 2012.

- Sirhindi, Ahmad. Maktubat-i-Sirhindi. Edited by Muhammad Abdul Ghani, Lahore, 1951.

- Shah Waliullah, Muhammad. Hujjat Allah al-Baligha. Delhi, 1785.